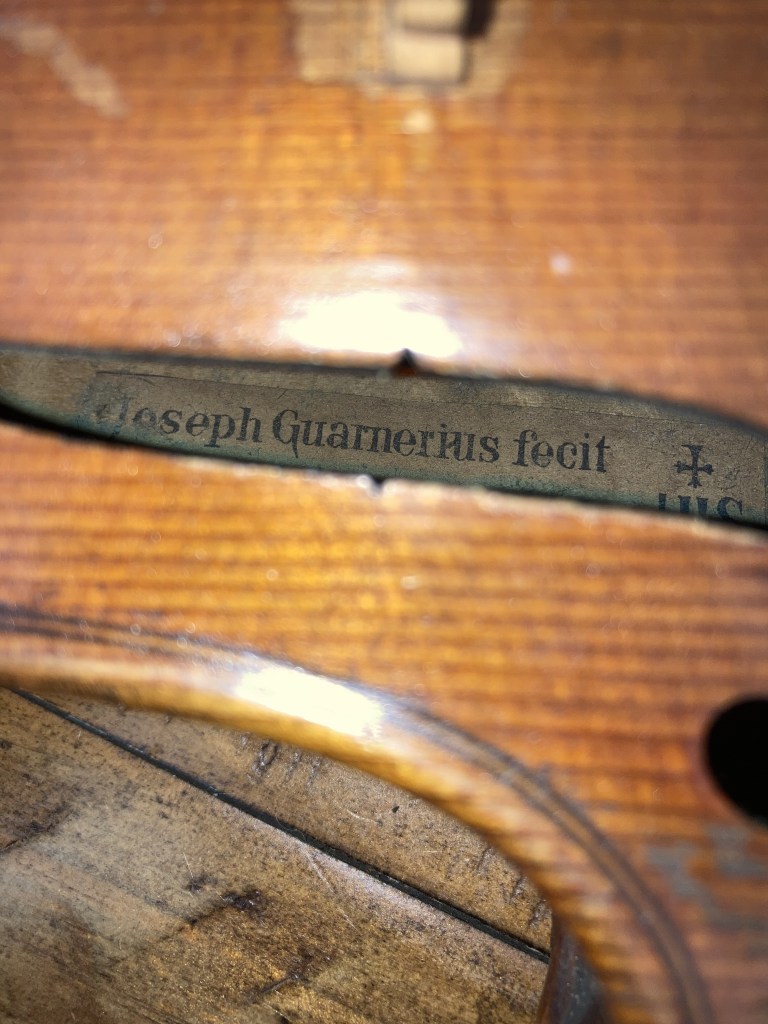

Time to finish up my deal on the red violin rebuild.

My goal for this project was to beat an inexpensive Amazon violin in fit, finish and sound. Did it work out? We’ll see as the piece progresses.

Alright, so after I glued the body back together (see last piece), it was time to do the final assembly. The pic above shows the gluing process for the new fingerboard. I ordered a pre-shaped fingerboard, a rosewood unit. “Pre-shaped” does not mean a perfect fit. I still spent an hour or two getting it to fit right, being very careful not to shave off too much material.

It’s easy to remove wood, and difficult to put it back.

This really is the story of this entire project. Caution and patience. I didn’t rush anything, because you can’t. Something bad will happen if you do this.

A case in point is the fingerboard. You can’t remove gobs of material from the fingerboard, because it is actually concaved .7mm from front to back- this allows proper resonance of the string as you play. .7mm is not a lot! If you get aggressive with rough sandpaper, the .7 is gone in a flash. Therefore, I sanded it with 600 and 1000 grit, and left it at that. Mostly I removed material from the sides for playability- the fit between the fingerboard and the neck is precision, it must be entirely smooth. This was difficult.

But eventually, it happened.

Then I moved onto the pegs. I have a special sharpener for these, it looks like an oversized kid’s pencil sharpener. What I didn’t realize was that the factory presets were entirely wrong for my violin, the blades were adjustable. Fortunately, I had a handful of very cheap pegs to practice on. I immediately destroyed three in my first attempts until I learned that I had to adjust the blades. Also, I found out that the taper of the individual instruments differs, so I had to customize the taper angle to get the pegs to fit well on my particular fiddle. Once I had it figured out, I carefully sharpened the rosewood pegs for this instrument. See below.

These were the first two. Note how they stick out- as the holes wear, the pegs get shorter. You have to lop off the ends to get it to look right. I fitted the four pegs, applied peg soap to keep them from slipping when tuned, and then drilled them with a 1/16in bit.

Once the pegs were done, it was time to move onto the nut, or the small block of wood that keeps the strings separated and at the right height for playing. Ideally, the G string will sit .4mm from the fingerboard, and the E will be at .3mm. Do you have any idea how small that is? One slip of the file and you are screwed! See below for how I started- I had to shape the nut, a tiny block of rock-hard rosewood.

This is what the nut looked like before I shaved it, but after I cut it to height. It still has its square profile. You can also see the final look of the pegs, trimmed, drilled and installed.

This is the final height profile of the nut. As you can see, it sits just a hair above the fingerboard. It’s actually slightly too high, but remember what I said about a single slip of the file? It’s a real thing. I decided this was good enough. It was time to groove the nut for the strings.

This guage came in super handy. It was easy to use. Just lay it on the nut, mark carefully with a pencil, then square the lines with my mini-steel square. Then came the hard part- the making of the grooves.

I took a deep breath, laid my machinist’s v file on the nut, and took sure strokes. Even exercising extreme caution was not enough. I think my D groove is a hair too close to the A. (The D groove is second from right, A is the third). However, it would have to do, there are no second chances unless you want to discard the nut and start over. This is precision work. Unforgiving. Also, I was a hair high on my G groove (extreme right)- this affected playability at the end of the project and probably needs adjusted at some point.

I must mention my special purpose, heavy violin clamp. This thing was awesome for the finish work. It kept the violin stable and straight, which was a lifesaver for the next step, shaping the bridge. See below.

Note how the fingerboard is a deep red color. This is because after the final sanding with 1000 grit I took a fingertip’s worth of olive oil and spread it around to bring out the color and woodgrain. Actually, this is a point of contention on violin message boards. There are those who say that any oil is heresy. Others buy super expensive finishing oil. One fellow said he uses the oil from his forehead. There are a lot of opinions here- people are passionate about their instruments!

However, a plurality said that regular olive oil is fine, used sparingly. So I did. To darken and protect the wood, all that you need is maybe three fingertips worth of olive oil to give a smooth, dry finish. You’ll know if you use too much. A greasy feel is to be avoided, and no oil must get on the varnish.

It was time to shape the bridge.

A word about bridges. Holy crap there is a bunch about this on YouTube! Everyone seems to have their own technique, and each violin has a custom bridge fitted to the individual instrument. There is no one-size-fits-all here because of individual top plate curvature and fingerboard height. There are accepted standard measurements for the feet width and bridge thickness, and I didn’t realize what hard, hard wood those things were made of until I shaped my very first one. See below.

One of the first things I did when I decided to start this project was to order a luthier’s tool kit from Amazon. I’m glad I did, I used almost every tool in the kit, one such was the bridge fitting tool you see above.

As you shape the bridge, top profile is crucial- the guage pictured above is useful in that regard. However, shaping the feet is important, too. You can see how this is done above. At first I tried fitting the bridge by hand by rubbing it back and forth on a coarse grit sandpaper. This gave terrible results, as the bridge’s feet are supposed to have no gaps when it sits at a 90 degree angle to the top of the plate.

Then I discovered this tool in my luthier’s kit- it clamps the bridge at a right angle to the plate, and it has a little wheel for when you move it back and forth on the sandpaper. The tool worked well, and eventually I got satisfatory results. I went from 220 to 600, and finally 1000 grit for a precise, gap-free (supposedly) fit. I never reached true gap-free status, but I got close.

After the feet were fitted, I cut the top. As usual, the top of the bridge was oversized and needed to be trimmed. Also, this violin’s fingerboard height was low, so the bridge needed extra trimming. After I got the correct height and profile, I trimmed and then beveled the bridge. After I beveled it, I cut the string grooves with the same file I used to cut the nut. See below- the bridge was as done as I was going to make it.

The last step was installing the sound post. This really sucked! I bought a mega-pack of blanks from Amazon, and it’s a good thing I did, because I went through three or four of them before I got the measurement right. The sound post sits just behind the treble foot (the right hand) of the bridge, and it connects the top plate to the bottom to transmit sound. You must insert it through the right F hole, stand it up, and snug it in gently. It is a friction fit, and it must stand ruler-straight. Crooked and funky is unacceptable.

Do you see all that can go wrong here? Trust me, every last thing did as I learned how to do this. It sucked! A pic below of one of my unsuccessful attempts- I was using a standard luthier’s soundpost tool, and the stupid thing kept falling off as I tried to stand it up inside the dark cavity of the violin’s body while working through a 1/4in wide slot.

Yes, that is electic tape wrapped around the stupid thing. I dropped the soundpost at least twenty times inside the body, that’s a real treat to get out of there, BTW. After fifty unsucessful attempts, I finally got the right length and developed a sucessful technique. It turns out that the best tool for installation is a standard hooked machinist’s scribe jammed into the post, and then you use the weird toothed end of the luthier’s tool to make adjustments to the sound post position.

The sound post must sit directly behind the right foot of the bridge, which must be placed directly between the notches on the F holes.

Did I mention that this was finicky work? Because it is.

Finally, all was ready for the final fit and adjustment. I placed the accesories on the violin and installed the strings. I put the strings on and semi-tightened them, then I walked away to allow everything to stretch and settle.

This is why sound post and bass bar installation is crucial. The left foot of the bridge rests upon the bass bar, and the right uses the sound post for support. As the strings tighten, the bridge is subjected to hundreds of pounds of stress- it must be perfectly straight and it must stand at exactly ninety degrees from the plate.

A note: During the rough tune, the strings will pull the bridge out of level. You have to constantly adjust it by careful shuffling.

A final word about this violin’s finish- in my last piece I mentioned that some numbskull had “restored” it in the fifties or something by applying a heavy coat of varnish. I debated whether I should strip this, because it could (and did) muffle the tone. In the end, I decided against it because first you’ll remove the original color. At the shop, the stain is mixed with the varnish, so if you remove one the other will go, too, and this violin has an attractive color. Also, you may do more harm than good. So I opted to remove a few of the worst offenders in terms of runs- literal drips and fish-eyes from the horrid second varnish coat. I did this via very fine sandpaper. 600 for coarse removal, then I stepped from 1000 to 2000, being careful to never cut into the original varnish or wood. It was the best I could do. The old varnish had to stay, so I applied a light coat of polish and left it as-is.

At long last, the red violin was ready to play and in its final configuration. See below.

It looked good- but how did it play? My biggest fear was that I’d make it pretty, but it would sound like crap. Did it meet my goal of outperforming an Amazon fiddle?

Why yes, yes it did.

I knew the first time I played it that this old student violin ran rings around a tinny 99 dollar Amazon thing, so for me this meant success. Yes, some things could be better, but those are nitpicks. Is this a concert grade violin? By no means. Fine tuning one of these is a real dark art, and I’ve just scratched the surface using YouTube, a lifetime’s worth of experience with tools, and patience. Lots of patience.

For my first attempt at a total overhaul of an antique and abused violin, it was good.

Thought to share this.